When gold was found in Australia, people came from far away.

Thousands of people came to look for gold.

This time was called the Gold Rush.

It was a hard life digging for gold.

Some people found big nuggets of gold.

Some people became rich but lots did not.

At a time when Australia was not yet a nation but still a number of separate British colonies, gold was discovered in a number of places, and the gold rush that followed changed our history.

The Australian Gold Rush 1851

In the early days, traces of gold had been found but were hushed by the government, in fear that convicts and settlers would abandon the settlements to seek their fortunes. However, in February 1851, a man named Hargraves found gold in near Bathurst, New South Wales, and word quickly spread. Within a week there were over 400 people digging there for gold, and by June there were 2000. They named the goldfield Ophir after a city of gold in the Bible. The Australian gold rush had begun!

The world’s largest producer of gold

Between 1851 and 1861, Australia produced one third of the world's gold.

By the end of the 19th century, Australia was the largest producer of gold in the world.

Heading for the gold fields ©Getty Images

So many people went to the goldfields that there was a shortage of people doing other work such as farming, building, baking and so on. Governor Fitz Roy was worried that there would be violence and lawlessness at the goldfields, and he ordered that gold seekers must pay for a licence in order to dig for gold.

The richest goldfields in the world

In August 1851, part of New South Wales was made into a separate colony, which was named Victoria after the Queen. Many Victorians had gone to the Ophir goldfields, and businessmen, in order to keep people from leaving the new colony, offered a prize of 200 guineas for the first person who found gold in Victoria. At around the same time, gold was found at Clunes, at Buninyong, and at Anderson's Creek near Warrandyte.

Towards the end of August 1851, James Reagan and John Dunlop discovered the richest goldfield the world has ever seen in a place the Aborigines called Balla arat, which means 'camping place', now the city of Ballarat.

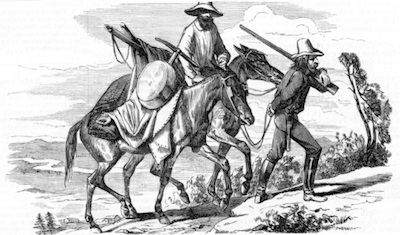

Travelling to the goldfields ©Getty Images

Other discoveries in the region soon followed in Mount Alexander, now called Castlemaine, in Daylesford, Creswick, Maryborough, Bendigo and McIvor, now called Heathcote. Thousands of people left their homes and jobs and set off to the diggings to find their fortune. At the start of the gold rush, there were no roads to the goldfields, and no shops or houses there. People had to carry everything they needed. They travelled by horse or bullock, or by walking with a wheelbarrow loaded with possessions.

By the end of September 1851 there were about 10,000 people digging for gold near Ballarat. By 1852, the news had spread to England, Europe, China and America, and boatloads of people arrived in Melbourne and headed for the goldfields.

The wealthy Bendigo goldfields were found by a woman, Margaret Kennedy, who saw gold in the creek bed in September 1851. She and a friend washed the gold using a bread-making pan. Within a few months, there were about 20,000 people searching for gold in that area.

Getting to the goldfields

People came from all over the world, intending to strike it rich and return home to their own countries. For many, the journey to Australia took seven or eight months, and on the cheapest fares, conditions were tough. There were many epidemics of illness on the ships, and those who survived the journey arrived at the goldfields weak and unfit for the hard life on the diggings.

Fresh food at the diggings was limited, and the basic diet was mutton, damper (a bread made of flour, water and salt, cooked over an open fire) and tea.

Clean water was in short supply because the diggers muddied the creeks, so cleanliness was difficult.

Also, sewerage was not disposed of in a sanitary fashion, and disease was common. There were a few doctors or chemists at the diggings, but not all were qualified. Many people died of diseases such as dysentery (an intestinal disease) or typhoid (a disease spread by bacteria in contaminated water).

There was violence on the goldfields. Thousands of people intent on making a fortune were all crammed together in a small location, in rough accommodation with few comforts, and tensions rose easily. There were fights, often over claim jumping. The journey to and from Melbourne was long and hard, and dangers included bushrangers who held up travellers and robbed them. The police were brutal, many were ex convicts who were looking out for themselves.

Life at the goldfields

Creeks muddied by sluicing. ©Getty Images

The space where someone was digging was called a 'claim'. To keep their claim, a person had to work on it every day except Sunday, so if no one was working a claim, someone else would take it. That was called claim jumping.

A few women came with their husbands and worked with them searching for gold, and some single women came to search for gold for themselves. Women could dig for gold without having to pay for a licence.

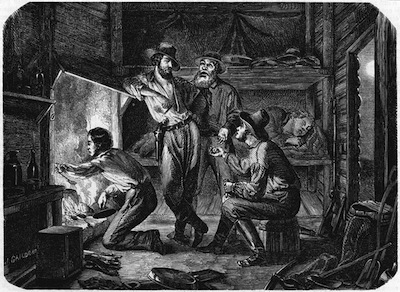

Diggers in their hut ©Getty Images

At the diggings, the gullies were filled with claims, and so the higher ground nearby soon became huge campsites. People lived in tents at first, but later on huts made from canvas, wood and bark were built.

Gradually there were stores and traders and other amenities, but life remained hard. Food and other goods had to be brought in by cart and so were very expensive. The settlements were all rather makeshift and temporary. Gold buyers and traders set up stores. Hotels and boarding houses were established, built of wood and lined with calico. The government camps were made of wood, and included a jail and accommodation for the soldiers. At some goldfields there were even theatres where travelling performers entertained the diggers.

A few people struck good finds of gold and became rich, but many did not. Mostly the people who did well were the tradesmen who sold food and equipment, or landowners who sold land to people who wanted to build homes and settle down after the gold rush.

Settlements at the goldfields. ©Getty Images

The lives of women at the goldfields

There were just a few women diggers ©Getty Images

At first there were mostly men at the diggings, but later on they were joined by their families. There were a few women who were diggers though, and there were women shopkeepers. Most women stayed home in towns with their families however, usually with very little money to live on, while their husbands travelled to live and work on the goldfields. A few years later, many women took their children and joined their husbands when conditions improved, although there were always more men than women at the goldfields, and life was hard for all.

©Getty Images

Women's work consisted of washing, ironing and cooking. They made bread, butter, jams, soap and clothes for the family. The living conditions were cramped, and there were few comforts at the diggings. Because the alluvial mining muddied the once clear creek water, clean drinkable water was hard to find. Often fresh water was carted in to the diggings and sold by the bucketful. Fresh vegetables and fruit were scarce and cost a lot.

Usually when a woman gave birth to a baby, she was assisted by other women. There was little in the way of medical assistance in cases of illness or to assist the women in childbirth. Many women died while giving birth. Epidemics of illnesses such as diphtheria, whooping cough, measles, typhoid and scarlet fever swept through the goldfields, and many men, women and children died.

There were women among the entertainers who travelled around performing at the various goldfields. The most famous of these was Lola Montez, best known for her Spider Dance. She was immensely popular wherever she entertained. Lola Montez was showered with small gold nuggets by the diggers whenever she finished a performance.

Lola Montez ©Getty Images

Chinese people at the goldfields

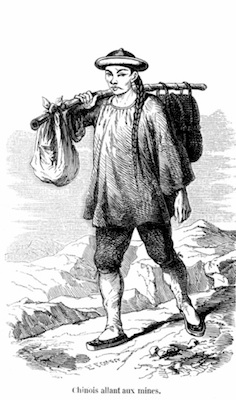

The Chinese prospectors walked from South Australia to Victoria ©Getty Images

News of the Australian goldrush reached China in 1853, when that country had been suffering from years of war and famine. To raise money for the fare to Australia, a man would take a loan from a local trader, agreeing to send regular repayments. His wife and children stayed behind, and worked for the trader if the man was unable to repay the loan. In an attempt to limit the number of Chinese at the goldfields, a law was passed in 1885 that any Chinese person entering Victoria would pay ten pounds tax and one pound for a protection fee, for the right to mine and live in the colony. No one entering Victoria from any other country had to pay this tax. However, this did not reduce the numbers of Chinese. They landed in South Australia and walked several hundred kilometres to reach the Victorian goldfields.

A Chinese temple at a goldfields settlement. ©Getty Images

When they arrived at the goldfields, the Chinese stayed together in large teams, usually from the same village, with a head man in charge. Groups were allocated duties such as mining, cooking, or growing vegetables for the team. The Chinese were generally very hardworking and honest, and were quiet and law abiding. They lived simply, especially as they were sending money home to repay their fare. Much of the alluvial gold was running out and the Chinese miners re-worked claims that had been abandoned, preferring not to go deep underground for fear of offending the mountain gods, and they collected gold that had been missed. They also saw other opportunities to make money, and worked at other jobs around the diggings, such as washing clothes, selling vegetables they'd grown, selling cooked food or herbal medicines and so on.

©Getty Images

There was ignorance about Chinese customs and culture, and the Chinese seemed very strange and different to the European diggers. The people at the diggings were suspicious of them and resentful of their methods of mining. The appearance of the Chinese, with their pigtails and unfamiliar clothes, their habit of going barefoot and of carrying loads hanging from bamboo poles carried across their shoulders, their religion, all made them the target of a great deal of racism and prejudice. Local Chinese societies came into being, to advise newly arrived Chinese about how to fit in.

Some Chinese returned home after the gold rush, but many stayed here. They found jobs, set up market gardens, restaurants or laundries. They brought their families to Australia. Gradually the Chinese became the accepted and respected group in Australian society that they are today.

A gold nugget. ©Getty Images

It’s a good idea to get information from more than one source!

See a map showing the Australian goldfields in the 1850s

https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/map/

Read more about the Australian gold rush

Sluicing to separate gold from the rocks. ©Getty Images

Read the kidcyber page about gold and methods of gold mining in 1850s

Read about women on the goldfields

http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/golden-victoria/life-fields/women-goldfields